Unconscious sexism on campus and at work

Posted by millis2 on Wednesday, December 16, 2015 · Leave a Comment

Imagine your coworkers criticizing how you say something or the sound of your voice. Now imagine being labeled as aggressive and power hungry instead of hardworking and dedicated. For women, this isn’t an imaginary concept.

Research suggests that men and women are assessed differently at work. According to a study at Stanford University’s Clayman Institute for Gender Research, these differences are a result of implicit biases, hidden beliefs about an individual’s capabilities, that can influence workplace decisions.

The data showed that women received 2.5 times the amount of feedback as men about aggressive communication styles, with phrases such as, “Your speaking style is off-putting.”

Joshua Raclaw, a post doctorate at the Center for Women’s Health Research, is a sociolinguist who studies conversation analysis and language as a social and interactional phenomenon.

His research looks at micro-level language use, such as turn-taking in group settings, interruptions, corrections, silence, word choice and gestures.

Raclaw’s current project examines possible race and gender biases in the peer review process for grants through the National Institute of Health for researchers in the STEM field.

“That’s our data source, we’re looking at how in the (peer review) meeting itself, these grants are discussed in ways that could kill a grant or get a grant funded,” Raclaw said. “Each grant they discuss for like fifteen minutes and that determines who gets $6 million in research funding for five years.”

Raclaw says other research has found gross inequality in the peer review process at a macro-level.

“Women get funded less frequently than men do. We know that researchers of color get funded far less frequently than white researchers, but we don’t really know the whys of this.”

Getting NIH research funding is critical for career trajectories. According to Raclaw, more and more women are reaching junior faculty level and falling out before reaching tenure, which Raclaw attributes to a lack of funding from these research grants.

Raclaw’s research specifically focuses on funding in STEM research fields, but a similar pattern of fewer women receiving tenure can be found across campus.

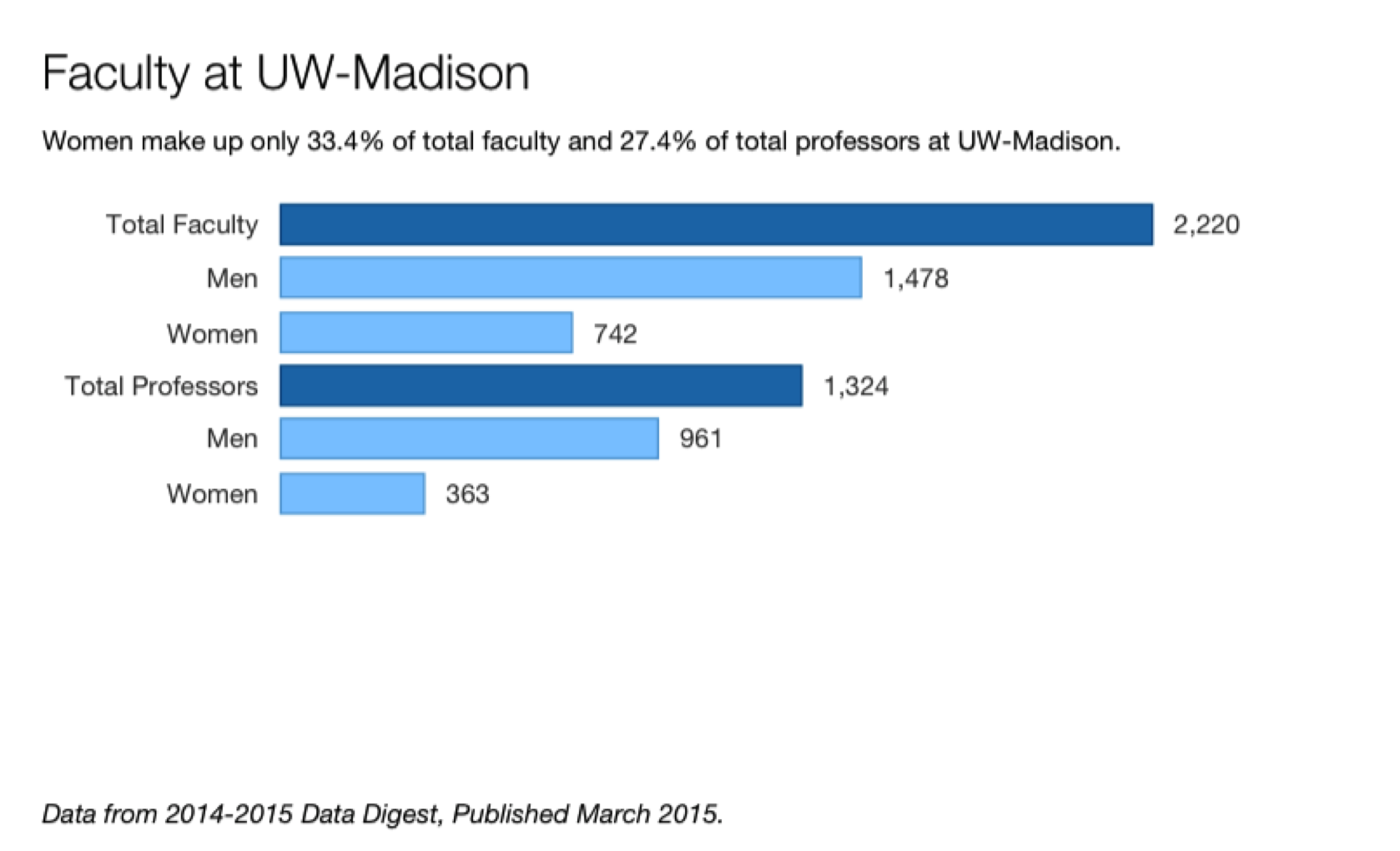

According to the UW-Madison 2014-2015 Data Digest, women made up only 33 percent of total faculty at UW-Madison last year. Of these women, only 27.4 percent are professors.

Sixty-nine faculty members were hired in the 2008-2009 year, including 18 women and 51 men. Of these groups, only 33 percent of women were given tenure promotions within six years while 57 percent of men were given tenure.

Bigger gaps are found among faculty in certain departments, based on data from the Women in Science & Engineering Institute (WISELI) at UW-Madison in 2014. Women make up only 15.1 percent of faculty in the physical sciences. There are eight departments throughout the university that have no female faculty members.

The data trends show greater gender gaps in the sciences than social studies and humanities.

A 2012 Yale study showed that physicists, chemists and biologists viewed young male scientists more favorably than young women and were significantly more willing to offer men the job. If offered to women, her starting salary was set at an average of $4,000 lower than his.

Gendered language

Social constructions of gender are also found in the way we use language and understand others.

In the early 1970s, researcher Robin Lakoff conducted groundbreaking research that led to the eventual foundation of the field of language and gender studies. Lakoff’s research led her to develop a concept called “Women’s Language.”

She asserted that society expects women to speak with features that she refers to as “powerless.” Her ideas are still the basis of research today.

“We recognize that not all men and women are going to speak the same way,” Raclaw said. “There are for example, powerful women CEOs that talk very very differently than men in the workplace that have less power.

One of the most significant factors regarding someone’s perception depends on whether they are in a traditionally male- or female-dominated field. A female working in information technology will be perceived very differently than a female working in education, even if her communication style is the same in both settings.

Certain traits are considered feminine or masculine and in turn, expected from males or females. Raclaw said taking an egalitarian approach to decision-making and aiming to make sure everyone’s voice is heard is perceived as a feminine leadership-style.

This is not because women are inherently prone to this type of leadership, Raclaw said, but because we see women using this type of decision-making more often. Women that don’t possess this style might be viewed unfavorably or considered overbearing.

This language can be found in the classroom setting as well. Setting and context, such as classroom dynamics and peer relationships, are hugely important, especially when considering the social environment of small groups.

Traits such as interruption and resisting new ideas are statistically seen more among men, said Raclaw, and therefore these traits are less likely to be challenged when exhibited by males than by females.

Sue Robinson, an associate professor in the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication, said that like language, implicit biases are complicated and other social constructs play a role.

Robinson reflected on her experiences of gender bias when working as a reporter. She referred to herself as S. Robinson to remove gender from her name.

“I had a city official come up to me once and tell me I had to smile more,” Robinson said. “I had another head of an academic department tell me that I should get a better haircut and that I shouldn’t always wear my hair in a ponytail.”

But Robinson did not complain about these comments.

“Your reaction in those moments is you need these people, you need to have a working relationship with them,” she said. “If you call them out, now you all of the sudden feel awkward, and there’s an avoidance that happens. As a reporter, or an academic for that matter, you can’t afford that.”

UW-Madison School of Business Faculty Associate Gwen Eudey also shared her experiences with gender discrimination in the workplace.

At the start of her career as a junior faculty member at Georgetown University in the early nineties, a senior male colleague slid a page under her door that needed to be typed. Eudey wrote a note stating he must have mistaken her for a secretary and slid it back under his door.

Today, Eudey says she hasn’t heard of that extreme of an example recently, but she still feels awkwardness when walking into a board room full of men.

“You have to take a deep breath and just kind of go. It’s just an extra hurdle. I love that expression, ‘lean in,’ you just have to do it,” Eudey said.

The concept of “leaning in” comes from Sheryl Sandberg, the Chief Operations Officer at Facebook. Her book, Lean In, discusses the barriers that women face in the workforce.

In a 2010 TED talk, Sandberg said, “Men attribute their success to themselves and women attribute it to other external factors. If you ask men why they did a good job, they’ll say ‘I’m awesome.’ Women will say someone helped them, they got lucky, or they worked really hard.”

Sandberg reflected on her childhood ambitions and being labeled bossy. A recent campaign called “Ban Bossy” wants to encourage young girls to be ambitious leaders and encourage them to be leaders without being labeled bossy.

“Bossy” is just one of many gendered stereotypes that label women. A Pantene commercial from 2013highlighted these double standards among men and women, illustrating how self-assured men are seen as authoritative and persuasive, while self-assured women are labeled bossy and pushy.

The 2003 Heidi Roizen study is an example of this double standard. Stanford Business School Faculty Associate Frank Flynn took the real life profile of Heidi Roizen, a Silicon Valley executive, and changed her name to Howard. He then distributed each version among two groups of students.

The results? Both groups found Heidi and Howard to be equally competent, but students preferred working with Howard over Heidi. Heidi was seen as more power hungry and self promoting. Flynn said that the more aggressive students thought she was, the more they hated her.

The only difference was her name.

An uphill battle

A 2014 report from The White House Council of Economic Advisors shows more women are earning college and postgraduate degrees at higher rates than men, and women are increasingly entering traditionally male-dominated occupational fields.

“Things do change,” Eudey said. “But there’s still a long way to go.”

Eudey says that to keep encouraging positive change, women students have to “lean in” more.

On a broader, macro-level, Raclaw believes we must change the culture of gender and implicit biases in society to combat certain forms of gender discrimination.

“It is an incredibly uphill battle, but what needs to be changed largely, isn’t necessarily how men and women speak as much as the culture of how we understand men and women to speak,” Raclaw said.

“I think the most important part, again, goes to culture,” Raclaw says, “and that’s a hugely difficult thing to change.”

Category: Social Justice, UW Problems · Tags: Gender, Inequality, Sofi LaLonde

The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.

-Martin Luther King Jr.

The Arc: Visions of justice

The Arc: Visions of justice